The Evolutionary Origin of Emotions

Nature photography and emotional regulation are deeply connected. For years, I have dedicated myself to understanding my emotions, their origins, and how to manage them in pursuit of well-being. Being a highly sensitive person is not easy in a historical moment where the pace of society does not allow us to pause and understand what is happening internally, while a cascade of overwhelming emotions is already waiting for a response.

Understanding my emotions has been a complex process, especially because during my training in biology, and in one of my greatest passions, evolutionary theory, I never saw emotions as a central element. Life did not originate in order to feel. In an evolutionary context, life did not need emotions to exist. At the origins of life, unicellular organisms detected resources, moved toward them, reproduced… and that was it. There was no sadness, no anxiety, no happiness, no questions. So why did emotions appear? Because life became complex, and with that complexity emerged a deeper, more existential dimension of the experience of being alive.

Emotions do not arise when life is simple; they arise when life requires decisions in uncertain scenarios. They appear when there are other individuals, cooperation, conflict, memory, and the possibility of a future that does not yet exist. In this context, emotions function as rapid decision-making systems in brains that cannot calculate everything rationally. They are evolutionary shortcuts that allow quick responses to complex situations, prioritizing action over exhaustive analysis. Before conscious reflection existed, fear already drove flight, sadness encouraged pause and recalibration, and emotional mechanisms such as attachment emerged to promote care. Far from being a mistake, emotions were an effective biological solution for surviving in a changing world, even though in modern life these same mechanisms can lead to overwhelming feelings.

These landscapes are not just places. They are the original context of the human mind. In silence, scale, and natural rhythms, the nervous system remembers how to rest. Photos›: Jhonattan Vanegas.

The first major changes in brain evolution were not related to reason or consciousness, but to the regulation of behavior in increasingly complex social contexts. As hominins began to live in stable groups, cooperate, care for offspring over long periods, and anticipate threats, certain brain regions (such as the limbic system) took on a central role. Emotions did not arise to make us feel, but to coordinate actions and increase survival probabilities in unpredictable environments. In this sense, emotions can be understood as biological solutions to concrete evolutionary problems; through emotions we generate feelings that allow us to reinforce bonds, protect offspring, recognize allies, avoid danger, and maintain group cohesion.

With the progressive increase in brain size and reorganization, especially from the genus Homo onward, emotional life ceased to be tied solely to immediate response and began to intertwine with memory, anticipation, and meaning. The development of language, symbolic thought, and self-awareness amplified emotional experience: fear was no longer felt only in response to present threats, but anxiety emerged in response to possible futures; loss was no longer momentary, but became prolonged sadness and grief. From this perspective, conditions such as depression or feelings such as anguish did not necessarily evolve to fulfill a direct adaptive function, but can be understood as inevitable byproducts of a brain capable of imagining, remembering, and reflecting on its own existence. The human mind did not appear suddenly, but as the gradual result of increasing encephalization that profoundly transformed how we experience the world.

This illustration represents the gradual encephalization of the human lineage, showing how brain size and organization increased from Australopithecus to Homo sapiens. The illustration were created using ChatGPT’s image generation tool.

Essential Emotions and Their Adaptive Role

Fear, Attachment, Anger, Sadness, Joy, and Disgust

The most important emotions in evolutionary history did not arise to make us happy, but to solve concrete survival problems in uncertain environments. The oldest and most fundamental of these is fear. Thanks to fear, organisms were able to detect threats and react quickly to predators, environmental dangers, or conflicts. Fear enabled flight, freezing, or defense before reflection was possible. Without this emotion, the evolutionary line would simply have ended.

Alongside fear emerged attachment, a key emotional mechanism in species whose offspring are born immature and require prolonged care. Attachment allowed caregivers to keep offspring close, protect them, and ensure genetic transmission. This emotional mechanism laid the foundations for social bonds, cooperation, and eventually love. Without attachment, there would be no community, and without community, no human evolution as we know it.

Anger, often misunderstood, played an important adaptive role. It allowed the defense of resources, the establishment of boundaries, and the regulation of conflicts within groups. Anger helped protect food, territory, and relationships, functioning as a primitive mechanism of justice and social balance. In ancestral contexts, expressing anger could mean the difference between being displaced or remaining within the group.

Sadness appears as a more complex emotion, linked to loss and failure. Evolutionarily, sadness allowed individuals to stop acting, reduce energy expenditure, and signal the need for support. It is an emotion of withdrawal and recalibration, inviting pause, reflection, and behavioral reorganization before continuing. It did not arise to punish, but to protect when something had gone wrong.

Disgust is one of the most ancient and bodily emotions we possess. It evolved as a preventive defense system, designed to keep us away from anything that could make us sick or kill us: decaying food, toxins, bodily fluids, or diseased bodies. Long before knowledge of bacteria or parasites existed, disgust was already doing its job, triggering an immediate visceral response that requires no conscious reflection.

Finally, joy or pleasure acted as temporary chemical signals that reinforced useful behaviors. Joy indicates that an action was beneficial and worth repeating, whether finding food, strengthening a bond, or cooperating with others. That is why it is brief and fleeting: its function is not to last, but to motivate. If it were constant, it would lose its adaptive power.

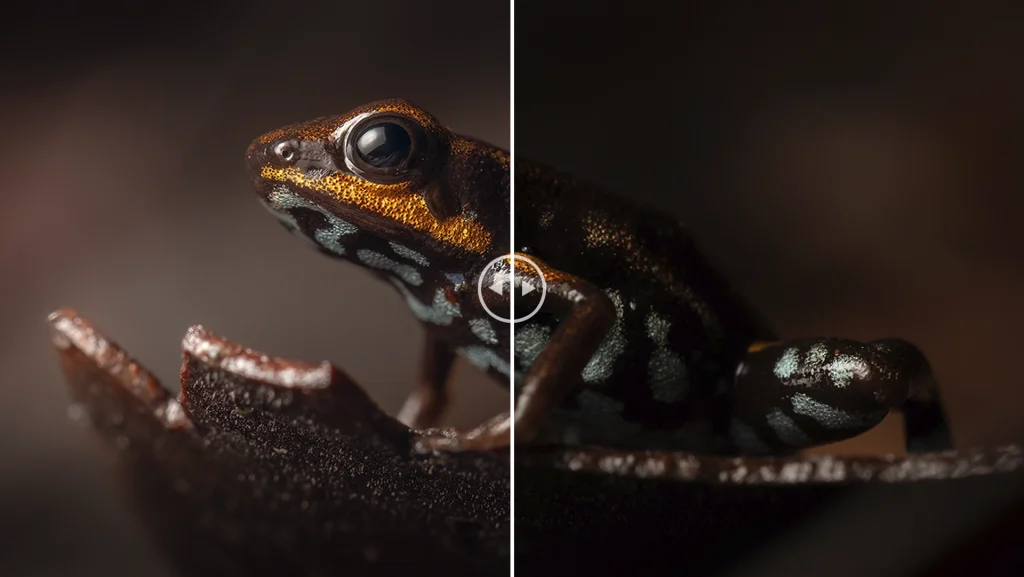

Fear, attachment, anger, disgust, and joy are not flaws of the mind. They are ancient biological tools that made survival possible. Photo: Jhonattan Vanegas.

As brain complexity increased, these basic emotions did not disappear but became amplified. With the emergence of memory, anticipation, and self-awareness, fear transformed into anxiety, sadness into depression, and attachment into profound grief. Not because the system is damaged, but because a brain capable of imagining the future and remembering the past can suffer even when no immediate threat exists.

In this sense, human suffering is not an evolutionary mistake, but the cost of an extraordinarily complex brain. Emotions did not evolve to give us existential answers, but to keep us alive. Meaning, on the other hand, does not come from biology; it is something each human being must construct through their capacity to feel, understand, and inhabit the world.

As the brain expanded, emotions expanded with it. Greater awareness brought both adaptation, and weight. Photo: Jhonattan Vanegas.

What Do We Do With the Ability to Feel Everything?

Consciousness did not arise to make us happy. It arose because it offered an adaptive advantage. It allowed us to simulate futures, learn from the past, understand others, and coordinate increasingly complex groups. However, this advance came at a profound cost. Consciousness allows suffering even in the absence of real danger. Other species suffer only when something happens; our species (Homo sapiens) can suffer by remembering, anticipating, or imagining. That is the price of a brain capable of understanding. Evolutionarily, there is no moral “purpose” to pain: evolution does not plan, care, or console; it simply filters what survives. But the fact that something lacks an evolutionary purpose does not mean it lacks meaning.

Meaning does not come from biology, but from what we do in spite of it. Evolution gave us imperfect feelings, a brain mismatched to the modern world, and a consciousness capable of pain, but it did not give us meaning. Meaning is not a property of the universe; it is a human response to the fact of being alive. Perhaps the question is not “why do we suffer?” but what we do with the ability to feel everything. Because feeling sadness, fear, anxiety, or love is also what makes empathy, compassion, art, care, and connection possible. In this act of questioning, of staring into the abyss and still continuing to ask, we are doing something profoundly human. Emotions did not arise to make us happy; they arose because a brain capable of feeling was the inevitable price of a brain capable of understanding.

In the contemporary context, emotional suffering takes on a different form. We live under the imperative of performance, constant positivity, and self-optimization, where exhaustion no longer arises from external imposition but from voluntary self-exploitation. The individual becomes both exploiter and exploited, fully responsible for success and, therefore, also for failure. In this scenario, emotional overwhelm does not emerge from prohibition but from excess; not from limits, but from infinite demand.

Unlike multitasking in wild species, an adaptive strategy to distribute attention and survive, multitasking in our species, within the modern context, fragments consciousness, dilutes meaning, and exhausts the nervous system. The pressure to be constantly productive, positive, and available leaves no space for pause, grief, or vulnerability, turning fatigue into a structural condition and emotional distress into a logical consequence of a world that no longer knows how to stop.

To feel everything is not a flaw.It is the cost of a mind capable of seeing far beyond the present. Photo: Federico Espinosa.

Why Being in Nature Calms the Human Nervous System

Nature does not calm us because it is beautiful. It calms us because it is the environment for which our brain was built. It is not that nature “does us good”; it is that we are a product of it. Everything else came later. Our brain is ancient, deeply ancient, and it was not designed for screens, cities, constant noise, endless decisions, or permanent social comparison. It was shaped over hundreds of thousands of years in forests, rivers, savannas, and jungles, through cycles of light and darkness and organic soundscapes. When we enter nature, we are not escaping the world; we are returning to the original context of the nervous system.

When we are in nature, hyperactivity in the prefrontal cortex decreases. The prefrontal cortex is the center of complex thought, judgment, identity, and constant questions about who we are and who we should be. It is the region responsible for rumination, anticipation, guilt, and anxiety.

Reduced Prefrontal Cortex Activity

In natural environments, the activity of this area decreases, particularly that associated with rumination. That is why, when we are in nature, we think less, judge ourselves less, and the “mental drama” quiets down. This is not magic or suggestion; it is cognitive decompression.

Activation of the Parasympathetic Nervous System

The parasympathetic nervous system is activated. Nature stimulates the system responsible for rest, digestion, and bodily repair. Cortisol levels decrease, heart rate slows, and muscle tension is reduced. At the same time, oxytocin increases, along with a sense of safety and emotional regulation. The body receives a simple and profound message: there is no immediate threat. And when the body feels safe, the mind can finally rest.

Involuntary Attention and Mental Restoration

Nature reduces the decision-making load. In cities and modern life, we choose everything, decide everything, and compare everything. This constant demand exhausts the brain. Nature, by contrast, offers simple patterns, gentle stimuli, and rich but non-invasive information. This is known as involuntary attention: observing leaves, water, movement, or light without conscious effort. In this state, the brain rests without shutting down, remaining present without the pressure to solve everything.

In nature, the mind stops scanning for threats and the body remembers how to rest. Photo: Alejandra Maldonado.

Returning to states that could be called primal, ancestral, or essential is not a regression, it is an alignment. When we are in nature, the body does not need to defend itself against symbols or artificial stimuli, and the mind does not need to maintain a constant identity. There is no “who you should be.” There is only presence, perception, and body. This state closely resembles how humans lived for 99% of our evolutionary history.

It is important to understand that nature does not eliminate pain on its own, but it does contain it. In a natural environment, suffering is not amplified by noise, comparison, or judgment. Sadness can exist without becoming identity, fear without turning into catastrophism, and anxiety can diminish as the body returns to the present. Nature creates a space where feelings can exist without overflowing.

Nature also reminds us of something essential. It does not demand success, productivity, or explanations. It simply returns a deep and simple message: you are alive, and that is enough for now. Observing cycles of birth, change, death, and regeneration tells the brain that none of this is a mistake, that everything is part of a larger process. That understanding calms something very deep.

When our sensitivity is high, we tend to feel everything more intensely. This happens because we allow ourselves to observe, understand, learn, recognize patterns, and perceive deep time. In nature, we do not just feel, we recognize. It is like returning to what is essential, knowing that this is our origin.

Unlike other forms of life, our species has the capacity for contemplation. In the wild, animals must distribute their attention across multiple tasks to survive: avoiding predators while feeding, defending territory, or reproducing. We, on the other hand, can stop and observe without immediate threat. This capacity for contemplation is a rare and powerful evolutionary advantage.

Connecting with nature is not fleeing the world. It is not escape. It is recharging the system in order to return, not indifferent, but able to remain sensitive without breaking. Nature does not calm us by removing our questions, but by allowing us to inhabit them without being destroyed. And that is a profoundly human evolutionary gift.

Being in nature is not escape. It is alignment, returning to a state where the body feels safe enough to simply be. Photo: Gustavo Acosta.

Nighttime Nature Experiences and Ancestral Awareness

Night excursions allow us to enter something even more ancient. Night touches layers of the brain that daytime cannot reach. During the day we live in control, evaluation, productivity, and social vigilance; night changes the rules. At a neurobiological level, sympathetic activity decreases, sensory perception becomes more refined, and the world grows quieter, slower, more intimate. But there is something deeper: night is the ancestral territory of fear and awe. For most of human history, night was dangerous, mysterious, and unknown, but also the time of fire, storytelling, bonding, and observation. When you enter the night with knowledge and respect, something crucial happens: fear stops being a threat and becomes presence. It does not disappear; it transforms. That process reorganizes the emotional system, integrates fear and curiosity, and restores confidence in the ability to be alive without total control. That is why herping, nocturnal rainforest walks, and their sounds do not break you, they align you.

Why Photography Amplifies Nature’s Emotional Effects

Photography amplifies nature’s regulatory effect because it forces the brain to inhabit the present with intention. It is not just looking; it is looking in order to understand. When you photograph, three processes are activated simultaneously.

Deep Attention

The first is deep attention, not the anxious attention of “a thousand things,” but sustained, focused, almost meditative attention. The brain stops ruminating because it has a concrete, sensory task.Embodied Perception

The second is embodied perception. You do not only look; you measure with the body, distance, breathing, pulse, balance, and this reduces the hyperactivity of abstract thought.Meaning

The third is meaning. The human brain suffers most when it cannot find meaning, and photography creates a silent narrative: this matters, this deserves to be observed. That is why photography is not about capturing nature, but about relating to it through attention and respect. And that is why it calms more than simply “going for a walk.”

Photography is not just seeing. It is attention with intention. Photo: Federico Espinosa.

Nature as Emotional Regulation, Not Escape

Nature can consciously become a form of emotional regulation rather than an escape. This is crucial. Nature can regulate or anesthetize, and the difference lies in how you enter it. When nature is used as avoidance, you go only to “disconnect,” you do not look at what you feel, and you flee from pain; that works only briefly. When it is used as conscious regulation, the process is different. Enter with a gentle intention, not a goal—not “I want to feel better,” but “I am going to be here with whatever arises.” Slow down before entering: do not arrive rushed, walk slowly, breathe deeply, observe without a camera first; the body needs permission to leave alert mode. And use photography as an anchor, not a demand. Do not look for the “great photo”; look for presence, textures, light, patterns, small gestures. The camera becomes a bridge between emotion and attention, not a source of pressure.

All of this works together because nature lowers the noise, night opens deep layers, and photography focuses the mind. Together they return to the nervous system an essential sensation: I can feel without breaking. And that is what we most need today. We do not return to nature to escape pain; we return to remember that we are strong enough to feel it without being alone. And when you understand that, sadness does not disappear and anxiety does not magically vanish, but they no longer rule you.

Being here is not about leaving everything behind, but about learning how to stay. Photo: Gustavo Acosta.

One Response

I completely agree with your point about emotions helping us make decisions in uncertain times. It really made me think about how slowing down, like we do when we’re out in nature with a camera, can help us not only process those emotions but also reconnect with the present moment.