Charles Darwin: Life And Work

By: Jhonattan Vanegas

Charles Darwin: Life And Work

On April 19, we commemorate the death of Charles Robert Darwin, the British naturalist who revolutionized biology by formulating the theory of evolution in his masterpiece On the Origin of Species, published in the mid-19th century. Modern evolutionists continue to return to Darwin’s work—a fact that comes as no surprise, given that the roots of contemporary scientific thought run deep through his legacy.

The cornerstone of the Darwinian paradigm is the theory of natural selection, whose formulation and defense were not Darwin’s achievement alone. A second name, often overshadowed, was crucial to this process: Alfred Russel Wallace, who independently developed a similar theory and staunchly defended the concept against the criticism of the time. Together, their ideas forever transformed our understanding of the natural world.

Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, pioneers of evolutionary theory. Although they developed their ideas independently, their shared insight into natural selection forever changed the course of science and our understanding of life on Earth.

Childhood Among Beetles And Constellations

On February 12, 1809, Charles Darwin was born—the fifth of six children to physician Robert Waring Darwin and his wife Susannah Wedgwood. His father, a wealthy and well-known aristocrat, ran the household with a firm hand, while his mother, practical in nature and artistically inclined, had a deep appreciation for all forms of art. His paternal grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, was a renowned philosopher, physician, and poet, author of Zoonomia, a work that outlined some of the earliest ideas on biological evolution, partially anticipating what his grandson would later develop.

In 1817, following the death of his mother, Charles was sent to school in his hometown of Shrewsbury, England. Surrounded by beautiful natural landscapes, it was there that his love for nature blossomed. He began collecting beetles, butterflies, shells, stones, stamps, and coins, and developed an early fascination with wildlife. He also grew fond of hunting, fishing, and experimenting with breeding domestic animals—experiences that would later influence his scientific thinking.

However, Darwin was not particularly outstanding academically: his school performance was modest, and his interest in formal studies was limited. His true education took place outdoors—in the fields, among insects, and through careful observation of the natural world around him.

Young Charles Darwin, surrounded by the wonders that sparked his curiosity.

“When I left school, I was neither very bright nor very dull for my age; I think my teachers and my father considered me a rather ordinary boy, perhaps below the average in intellect.”

Edinburgh and Cambridge: The Awakening of a Restless Mind

In 1825, at just 16 years old, Charles Darwin was sent by his father to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, following the family tradition. However, his disinterest in lectures and his horror at surgical procedures without anesthesia led him to abandon the career. Nonetheless, his time in Edinburgh was not wasted: he actively participated in scientific societies such as the Plinian Society, where he presented his first works on marine organisms.

In 1827, after discussing his future with his father, Darwin transferred to the University of Cambridge to study theology, aiming for a respectable life as a clergyman. But once again, his true passion ignited in a different direction: nature. It was there that he met two key figures: John Steven Henslow, a botanist and clergyman, and Adam Sedgwick, a geologist. Henslow taught him the importance of detailed observation, while Sedgwick showed him how to derive laws from facts. Both would awaken in Darwin his genuine scientific vocation.

During his time at Cambridge, he became an avid collector—especially of beetles—and an enthusiastic reader of scientific works. He was deeply inspired by Humboldt’s Personal Narrative, which fueled his desire to explore exotic lands.

Although he ultimately earned a degree in theology, his future would not lie in the pulpit. Despite his initial religious beliefs, a scientific spirit seeking something beyond dogma was already emerging within him. Henslow, ever perceptive, recognized that Darwin was destined for science, not the Church, as Darwin would later write:

“At that time I did not in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible; I soon convinced myself that our Creed must be fully accepted.”

Charles Darwin in his early academic years, caught between medicine and theology.

The Voyage Of The Hms Beagle: The Birth Of An Idea

In 1831, at just 22 years old, Charles Darwin received an invitation that would change his life: to accompany the captain of the HMS Beagle on a scientific expedition around the world. Although his father was initially reluctant, his uncle Josiah Wedgwood supported the idea, and Charles obtained the necessary permission.

Captain FitzRoy nearly rejected him due to the shape of his nose—believing in the pseudoscience of physiognomy—but Darwin’s enthusiasm and refined manners convinced him otherwise. Despite receiving no salary, Darwin accepted the challenge and covered the costs of his participation himself. The Beagle set sail in December 1831. Although Darwin was eager and excited, he soon faced a constant torment: seasickness, which plagued him for much of the voyage. Everything changed, however, upon reaching South America, where he devoted himself to collecting fossils, animals, plants, and recording natural phenomena with obsessive dedication.

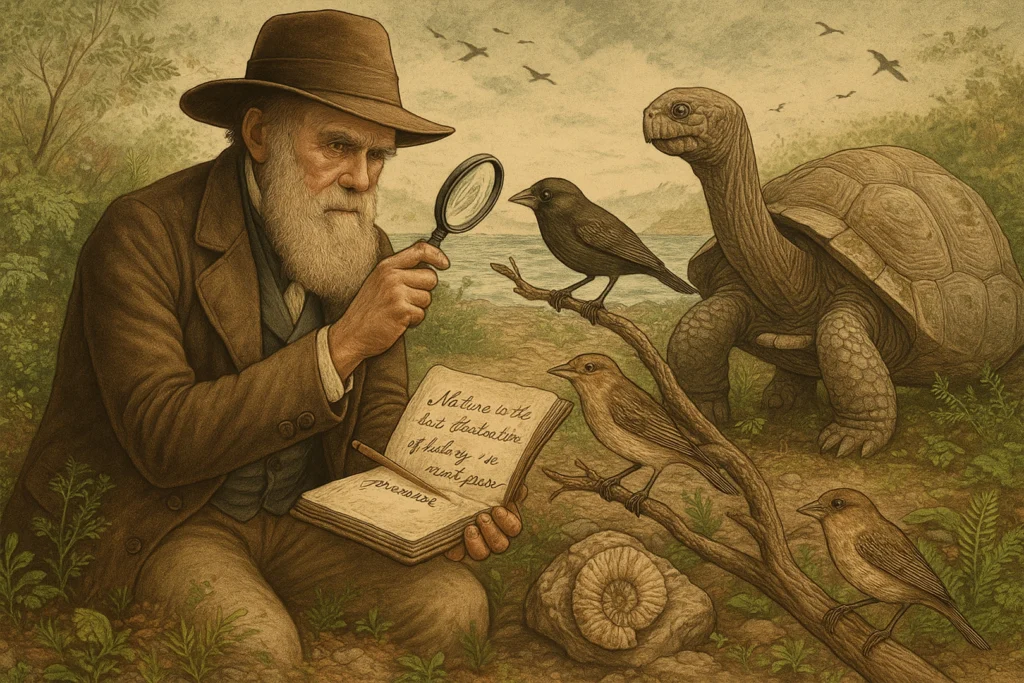

He discovered fossilized seashells atop mountains, giant fossils like the Glyptodon, and witnessed dramatic events such as the Concepción earthquake in Chile (1835), all of which began to undermine his belief in the stability of the Earth and its species. Influenced by Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, he began to conceive of a world in transformation. The most decisive moment came in the Galápagos Islands, where he observed tortoises and finches whose characteristics varied from one island to another. These differences suggested that species were not fixed, as the Bible taught, but could evolve. In his notebook, he wrote:

“Here in the Galápagos Islands, both in time and space, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact—that mystery of mysteries—the appearance of new beings on Earth.”

Upon his return to England in 1836, after five years at sea, Darwin was no longer the insecure young man who had embarked on the journey, but a respected naturalist, with an extensive collection of over 5,500 specimens and deep doubts about the immutability of species.

Welcomed into the scientific elite, he joined the Geological Society. But in secret, he had already become a transformist: he believed that species could change. The question that now obsessed him was:

What is the mechanism that drives that change?

Inspired by artificial selection in domestic animals such as pigeons and horses, Darwin began to wonder whether nature might also “select” certain traits. And so, the ideas that would later revolutionize science with his theory of natural selection began to take form.

Darwin aboard the HMS Beagle: the journey that changed everything. From seasickness to scientific epiphanies, it was during this five-year expedition that he encountered fossils, earthquakes, and the wildlife of the Galápagos—clues that would lead him toward the theory of evolution by natural selection.

The Birth Of The Theory Of Natural Selection

After returning to England, Charles Darwin definitively set aside his religious vocation and devoted himself entirely to science. With the support of Henslow, he began classifying the specimens collected during the voyage of the Beagle, which earned him significant recognition within the scientific community.

He collaborated with scientists such as Richard Owen—who would later become his rival—and John Gould, both of whom helped him describe and publish his findings in the work Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle. He also wrote his own account of the journey, Journal of Researches, considered one of the greatest scientific travel books of all time, and highly praised by Alexander von Humboldt himself. During this period, he published three key scientific works: Coral Reefs (1842), Volcanic Islands (1844), and Geological Observations on South America.

Darwin also formed connections with influential scientists like Sir Charles Lyell, whose principle of uniformitarianismdeeply shaped his understanding of natural change, and with Joseph Hooker, a botanist who became a close friend and the first person to whom Darwin confided his ideas about evolution. While analyzing his collections, Darwin concluded that species were not immutable, but rather changed over time, as shown by the Galápagos finches and fossils of animals resembling armadillos.

In 1837, he began to write down his ideas on species transformation in a series of notebooks titled The Transmutation of Species. Gradually, he shaped what would become his greatest contribution to science: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

The decisive moment came in October 1838, when, after reading Thomas Malthus’s essay on population, Darwin realized that in the struggle for existence, the most favorable variations would be preserved, while the less fit would disappear. This revelation allowed him to articulate the mechanism that would underpin his entire theory.

“At last, I have a theory to work with.”

— Charles Darwin

Darwin shaping the theory of natural selection. Back in England, surrounded by fossils, notes, and correspondence, Darwin began to connect the dots—transforming observations from his voyage into one of the most profound scientific theories of all time.

The Origin Of A Scientific Revolution

After discovering the mechanism of natural selection in 1838, Charles Darwin took nearly three years to draft the first summary of his theory. The document, 35 pages long, was later expanded into a 230-page essay in which he included a vast amount of data to support his ideas. Although he valued this essay deeply—so much so that he left instructions for his wife to publish it if he were to die—he chose to share it with no one except his friend Joseph Hooker.

For more than a decade, Darwin focused on gathering additional evidence before making his theory public. In 1856, encouraged by Hooker and Charles Lyell, he began to write a monumental work titled Natural Selection, which he envisioned as four or five times longer than the version that would eventually be published.

However, in June 1858, an unexpected event changed the course of events: Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace,

The birth of a revolution: Darwin and the theory of natural selection. Fueled by years of research and inspired by Malthus’s ideas on population, Darwin finally unveiled a mechanism to explain evolution—forever altering how we understand life on Earth.

a young naturalist who, independently, had arrived at a theory strikingly similar to Darwin’s own on evolution by natural selection. Wallace requested Darwin’s opinion on his manuscript. Distressed, Darwin acknowledged their shared priority, and after consulting with Hooker and Lyell, agreed to a diplomatic solution: a joint publication.

Thus, on July 1, 1858, both Wallace’s text and a summary of Darwin’s were presented at the Linnean Society of London, marking the public birth of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Prompted by this development, Darwin focused on writing a more concise version of his theory, which he completed in just three months. It was published on November 24, 1859, under the definitive title: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The book was an immediate success and caused a profound transformation in humanity’s understanding of life.

In the years that followed, Darwin revised and expanded The Origin in successive editions, and published over a dozen other books exploring various aspects of evolution, such as variation in domesticated animals, the expression of emotions, and the coevolution between plants and insects. His legacy not only changed the field of biology but also offered humanity a new way to understand itself and the world it inhabits.

Conclusions And The Legacy Of A Transformative Theory

Charles Darwin was the first to unify a wide range of facts and observations under a single, coherent theory capable of explaining the diversity and change in forms of life: the theory of evolution by natural selection. While other naturalists had intuited parts of this idea, only Darwin succeeded in integrating them into a solid and well-founded explanatory framework. He devoted nearly his entire life to gathering evidence, studying its consequences, and exploring its implications in nature.

One of the key pillars of his thinking was the direct influence of Charles Lyell and his work Principles of Geology. Darwin adopted Lyell’s concept of uniformitarianism—the idea that current geological processes are the same as those that acted in the past—and extended it into the biological realm, understanding that evolutionary changes were also gradual and cumulative.

In 1838, after reading Thomas Malthus’s essay on population, Darwin realized that limited resources created a struggle for existence, in which the fittest individuals survived and passed on their traits. This revelation allowed him to organize his thoughts and articulate the mechanism of natural selection, writing:

“All species have the capacity to increase explosively… the limitation of resources acts as a powerful selector… at last I have a theory to work with!”

Contemplating the Tree of Life: Darwin’s enduring legacy. In his final years, Darwin understood that evolution was not a ladder, but a vast, branching tree—each species a twig, all connected by a shared origin in the ever-changing story of life.

Impact and Controversy

On the Origin of Species sparked a true intellectual earthquake. Although Darwin did not explicitly address human evolution in the book, the implications were unavoidable:

Humans also share an evolutionary origin with other species.

Humanity’s position in the universe had to be reconsidered.

The literal interpretation of Genesis was deeply challenged.

Some of his harshest critics were former allies, such as Richard Owen, but passionate defenders also emerged—most notably Thomas Henry Huxley, known as “Darwin’s Bulldog.”

Darwin and Huxley: science, controversy, and conviction. While Darwin avoided public debates, it was Huxley who took to the front lines, fiercely defending evolution and reshaping humanity’s place in nature with the weight of evidence and reason.

The Darwinian Vision: A New Way of Understanding Life

For Charles Darwin, the true evidence of evolution was found in the fossil record, biogeography, and comparative anatomy. His proposal that geographic isolation acts as a driving force of speciation, along with his observations of unique adaptations in environments such as the Galápagos Islands, were fundamental in explaining how new species arise from common ancestors.

Through years of meticulous observation, tireless data collection, and deep reflection, Darwin forever changed our understanding of the living world. We no longer view life as a fixed design, but as a dynamic process, shaped by environment, time, and the relentless struggle for survival.

His theory of natural selection revealed that all species are connected by ties of common ancestry, and that each organism alive today is the product of countless generations of small, accumulated changes. Thanks to Darwin, we now understand that biodiversity is in constant transformation, and that the history of life does not resemble a ladder with a final destination, but rather an immense branching bush, full of divergences, adaptations, and extinctions.

In this new framework, humanity is no longer the absolute center of the universe, but one species among many, born of the same natural processes that gave rise to all forms of life. This vision does not diminish our worth, but calls us to humility, responsibility, and awareness of our place on the planet. And so, after more than a century and a half of discoveries and unanswered questions, the great question Darwin left us remains as alive as ever:

Are we human beings the pinnacle of evolution, or merely a twig on the vast, branching bush of life?

The Darwinian vision: life as a branching, ever-changing story. From fossils to finches, Darwin’s observations revealed a dynamic natural world—one in which all species are linked through time by common ancestry and shaped by the forces of evolution.

Note. All the illustrations featured in this blog were created in collaboration with artificial intelligence, using ChatGPT’s image generation tool. Each scene was thoughtfully designed to visually complement the content, honoring the scientific spirit and exploratory legacy of Charles Darwin’s life and work.